What happens when a visionary and an icon meets? What conspires when two architects from different generations, of diverse philosophies, come together? An exchange of ideas, visions, philosophies, the future of cities, the meaning of architecture and so much more. Over the years, we’ve brought to you our vision of architecture and design. This issue, we decided to take a backseat, and play spectators to a conversation between two creative geniuses. We brought together an unlikely duo for this interaction – Architect Hafeez Contractor and Architect Akshat Bhatt. Their practices, their approach, their experience might be divergent, but their thoughts and their perspectives seemed to meet at many junctures. The conversation that conspired covered not just architecture and design, but also urban planning, sustainability, policies, politics, and of course, the future of Indian Habitat.

What started off as a conversation between a young visionary and the architect who’s credited to defining the design identity of 21st Century India soon progressed into one of the most interesting dialogues in architecture we had ever witnessed. They met for the first time, but the meeting ended with them poring over Contractor’s most prized possessions – his sketchbooks that documented almost every single creative thought he had.

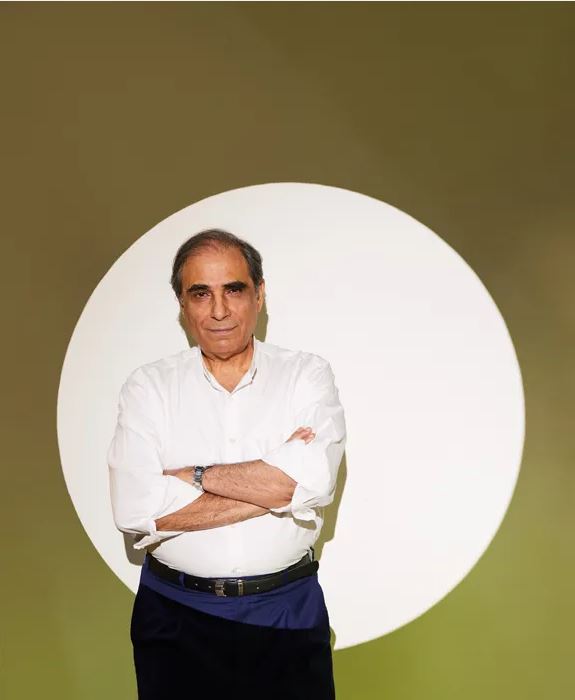

The duo met at Architect Hafeez Contractor’s office at Bank Street, just around the corner from the Mumbai Stock Exchange. The office speaks pure business, in stark contrast to Contractor’s futuristic, flamboyant projects. The office houses nearly 500 employees, making it perhaps the busiest architectural offices in the country. It is from this unlikely office, that the Padma Bhushan Awardee, creates his unapologetically flamboyant creations. His most famous projects include DLF Cybercity and DLF 5 In Gurgaon, Delhi, the Hiranandani Gardens, in suburban Mumbai, not far from the airport, where Contractor designed the domestic terminal. This neighbourhood certainly bears its architect’s signature flamboyance. The project illustrates Contractor’s inane ability to create a parallel world – it houses more than 15,000 people and includes offices for more than 150 companies; it has its own school and its own hospital. For Tech giant Infosys, he built a software-development campus outside Pune that features two avant-garde office orbs, and a 337-acre corporate educational facility near Mysore that is laid out around a columned structure. In New Delhi’s D.L.F Cyber City he constructed a sprawling office development for blue-chip companies including Ericsson, Star TV, GE, Standard Chartered, R.B.S, Oracle, Indus Tower, KPMG, Lufthansa and American Express. His portfolio also includes some of the tallest structures in the Subcontinent, The Imperial Towers, Mumbai; 23 Marina, Dubai, and the iconic Main – 42 in Kolkata.

“We do not ascribe to a signature style. We do every type of project like ultra-modern buildings, gothic buildings, and many. We are not limited to any particular style, for me style is a derivative of construction materials. Our style is driven by the requirement and aspiration of a client. We do not impose our designs on the client, instead we take the client’s vision forward through our approach and style.”

— HAFEEZ CONTRACTOR

With ongoing projects in nearly all the major cities, and countries abroad, 2500 clients, and nearly 500 employees, Contractor is no less than a legend in Indian architecture. His architecture does not conform to a style or a definition. He responds to the need and the context. But in this process, the architect created a distinct identity for 21st Century India. Once referred to as the ‘Slumdog Millionnaire Architect’ in a New York Times Op-ed, he’s perhaps the only Indian architect who has managed to penetrate the psyche of the masses. His high rises, townships and institutions, civic redevelopment projects and low-cost housing projects, are equally ground-breaking. It’s hard to believe that someone who was chided as a student for wasting his time sketching, would grow up to become India’s most spoken-about architect and one of the biggest advocates of slum redevelopment in India.

For Akshat Bhatt, founder and principal at Architecture Discipline, a practice that is quickly gaining ground as the progressive voice for architecture in India today, the discussion was an opportunity to compare notes on several ideas that both architects have grappled with in their careers. These included understanding “how architecture could be made accessible to the masses,” thoughts on sustainability, urban planning and everything that pertained to the business of architecture.

“Architecture should be for the people. That is why we involved ourselves with the design of the Mohalla Clinics in Delhi. We thought it was about time we started changing the city bit by bit with good design and architecture. The most strategic feature of the Mohalla Clinic is that it uses discarded shipping containers to solve an important socio-economic problem—access to primary healthcare.”

— AKSHAT BHATT, Founder, Architecture Discipline

Bhatt’s approach to architecture is thoughtful, but his designs can be bold, edgy, and progressive. “In my second year in architecture school, I came across a roof top extension by Coop Himmelb(I)au in my college library, which made me realise that architecture can be progressive and that there is more to it than block-work and organic settlements.” After graduating from the TVB School of Habitat Studies and The University of East London, and brief stints with Penoyre & Prasad and Jeff Kahane & Associates in London, he set up Architecture Discipline in 2007. Today, Architecture Discipline is recognised not only by its projects across the country, but also by its unique barcode logo that reads the firm’s name, address and contact details. The practice’s work is driven by a context-centric, rational approach to ideation, which is then defined and developed by a highly technical outlook with a focus on flexibility and longevity.

Notable projects include the multi award-winning Mana hotel in Ranakpur, Rajasthan; the Discovery Centre, a town hall for the Bhartiya City township in Bengaluru, the India Pavilion at the Hannover Messe in Germany which was adjudged the best pavilion in the 65-year history of the Messe, and the Corporate Headquarters for East India Hotels, the flagship company of The Oberoi Group, in Gurugram. Critical commissions on the urban scale include JDH, an urban regeneration project within the Walled City of Jodhpur; and the Mohalla Clinics, neighbourhood-level, primary healthcare facilities for the Government of Delhi.

As the two architects, who couldn’t have been more different, engaged in a conversation, we relegated ourselves to the background, as mere spectators, without even playing the role of a catalyst in the dialogue. Here, we present an edited version of the interaction.

THE MAKING OF A LEGEND

Akshat Bhatt (AB): You’ve been on top of the discourse of mainstream Indian architecture for the last 5 decades. There’s not been a single decade that your work hasn’t featured in architectural dialogues. To stay consistent, to be relevant, to be ahead of the game throughout is something that most architects aspire to be.

Hafeez Contractor (HC): I am an architect, who always feels that the need of a client is of paramount significance as it comes out of necessity and my role is to satisfy that need rationally. There are constraints, always. It could be time, space, money, but my job is to overcome all those hurdles, and give the client what he wants. Architecture should be honest and must respond to the spirit of the time characterised by distinct ideas, disparate missions, contrasting convictions and divergent preferences. It is this enduring belief that brought me to where I am today. One has to adapt to changing times and changing requirements. I don’t let myself be crippled by rules. I let the requirement govern the way I approach a project. And you have to respond fast, else it would be a lost opportunity. I also believe that if you have the talent, your talent has to be known, you have to be known. And to project your talent one must not hesitate to give freely. Let me give you an example. I was at a restaurant when I saw Narayana Moorthy seated there, unassuming as ever. I requested him to take a look at my work and expressed a desire to work for him. And I did. It was an unforgettable experience working with him. You have to constantly reinvent yourself.

Early in my career, when I was working with my cousin, there was this lady who approached us to design her home. We gave her a couple of design options but she didn’t like any. She came back with a picture of a beautiful, old-fashioned bungalow. We told her it’s not modern architecture. But that was what she wanted. When we refused, she left unhappy. That was almost a cathartic moment for me. I realised then that my duty, or role as an architect is to ensure that my client is happy. What am I without my clients?

For instance, when I entered the construction industry, all the buildings were leaking. I got rid of it by giving the buildings a raincoat. I reduced the external wall thickness from 9inches to 4.5inches and created another wall with a gap of 2ft-6inches, not only increasing floor space but also creating facades that never allowed the internal walls to get wet. I called it the 2ft-6inch architecture. It all boils down to responding to the need.

For me, work is not work, I feel like I am playing a golf match – when you defeat your opponent, you feel happy. Similarly, at work, when I accomplish something I feel elated. I work through the year and I do all kinds of work. I make iconic structures when needed, I do modest structures in mud and stone when needed. I do skyscrapers, hospitals, commercial buildings, a 250 sqft home and at the same time a 5000 to 30,000 sq ft residence. The ultimate question today is – how fast and efficiently can you work so that the buildings can be completed on time and economically.

In school, I wasn’t a good student. I would end up drawing bikes, guns, and forts during classes, and would be reprimanded by my English teacher. She told me I was a useless student, but one thing she said left me intrigued: “When you grow up, become an architect. I didn’t even know what the term meant, back then! But here I am. The point is, I have always enjoyed designing and I continue to do so.

AB: In the past five decades your practice has grown—from being a modest set up to being a large firm with nearly 500 employees. Are you creatively invested in all the projects your studio is commissioned for?

HC: I am involved in every project. Every project starts with a sketch. Every project is a Hafeez Contractor project in degrees. If I have faith in one associate, then my intervention will be little; with others, it will be different. As soon as I see someone is very capable, I put him in charge of a separate group. I keep forming similar groups. A senior person has four to five groups under him. This ensures that everybody does his work well, is earning well and is happy.

THE ROLE OF AN ARCHITECT

AB: I feel it’s time for a revolution. Architecture must address the needs of the common man, our cities, and habitats a whole. Issues of sustainable development, the environment – built and unbuilt, energy and the burgeoning population cannot be met by a traditional architectural approach. We have to address these at two levels, a long cycle of development, which means larger, slower interventions on one hand,and an immediate tactical response on the other. Don’t you think it’s about time architects stop pretending to think about the world and start thinking about the world?

HC: Yes. Absolutely. There are larger issues, of transport, of sewage, of housing, that need to be tackled. And a lot of architects are doing that. When I started off as an architect, soon after college, I would often be chided for taking up certain work. In college we were taught all about architecture, all about buildings. Right from my early days, I had decided, if someone comes to me with a request, and if I am able to do it well, then I will do it. In that sense, for me architecture was about service. I had decided early in my career that as an architect, I would be working for the people. And in that sense, for me, architecture should be for the people. In fact the clients brief and restrictions result in good Architecture.

When I started my practice, the issues I faced were more basic or rather elementary in nature. The problem of housing for the masses cannot be solved by creating a housing project in the outskirts of the city. When I ventured into the real estate sector, when I started working with builders, all buildings were leaking, each and every wall was leaking. My solution for this was the double wall concept. But no one was willing to implement this, because it was expensive. I gave them a solution wherein although they spend more, they earn more as well. When you are able to navigate all the constraints – the budget, space, time – and come up with the solution, for me, that is what good design is all about. Architecture should be able to give a solution, should be able to address the need of an individual or a larger population with a certain immediacy, urgency. That’s when it makes a difference. The future of India lies in how we build, how we build our cities, and house all our people.

AB: True. Architecture should be for the people. That is why we involved ourselves with the design of the Mohalla Clinics in Delhi. We thought it was about time we started changing the city bit by bit with good design and architecture. The most strategic feature of the Mohalla Clinic is that it uses discarded shipping containers to solve an important socio-economic problem—access to primary healthcare. These clinics are prefabricated with minimal on-site construction and can be rapidly deployed. The design capitalises on the structural strength of a discarded shipping container and works with it as a module, reducing the need for costly modifications or custom-built additions. In this manner, it redefines post-industrial waste as a medium for universal affordable healthcare.

We also worked on a system of automated transportation pods. The current crisis, given the extent and widespread external effects on urban mobility, comes with a possibility of renewed distrust of public transport in its existing form. With concerns around personal proxemics, social distancing, health and safety, the comfort/speed of destination to destination transit might usher an increased rush into acquisition and use of personal vehicles. The current models of urban public and private transport need to evolve using technologies and alternate models for mobility(micro-mobility as well as macro-mobility) with a new set of parameters that integrate the benefits of the personal vehicle while offsetting all the disadvantages of the same, thereby discouraging the use of the personal vehicle for travel.

I think, now more than ever, architecture and planning in general is no longer just about making a building. It’s about how we handle titular consumption in the city, how we handle transport, how we minimise fossil fuel consumption and emissions. You have to be conscious about energy. In that effect, architecture should be mindful of how to reduce the footprint of our consumption as a population. Because the conventional approach to development has resulted in cities that are not healthy places to live.

HC: One should be mindful of three key aspects – the first one, of course is speed, the flexibility you offer your clients, do not try to impose your designs on them, and lastly, not being cynical about what the clients want. Metaphorically speaking, there’s no reason to make a person who is hungry wait for hours for a Michelin-star meal, when all he wants is some food to satiate his hunger! And that sense of immediacy and urgency is what all architects should understand. There’s no point in delivering a building that’s 10 years too late! Clearly, it’s time for an architect to graduate from just designing a building to providing a service, or championing a thought process or a concern. I think that’s where the architect’s role, especially in today’s day and age, becomes more pertinent. There’s no point having conversations if you don’t have the skills to translate it into reality.

DECODING URBAN INDIAN HABITATS: THE REALITY AND THE VISION

AB: You’ve been vocal about your thoughts on social housing. In many of your interactions you’ve expressed that your purpose as an architect is to provide housing for every Indian. Slum redevelopment is a subject you are passionate about. You’ve also been instrumental in introducing a Slum Rehabilitation Scheme?

HC: When I pioneered the double-wall concept, there were articles which proclaimed – The Changing Horizon of Indian Architecture. But all I did was respond to the need. I’m not into making pretty pictures. Pretty pictures are just an outcome of good architecture. Over the past few decades, I’ve designed homes, commercial complexes, roads, but that’s not the real India. Today, in India, the most pressing aspect is that of the environment. What we do in the coming twenty years is going to define the future, it’s going to impact people’s lives. Our actions today will govern the future of our coming generations. We are a population of 1.3Billion. 70% of our people don’t have proper houses. We are talking about a 5 trillion economy, but more than half the population don’t have access to proper sanitation. My purpose, as an architect, is to give them access to proper housing.

I used to always say something should be done about the slums. And I always thought that the best way of dealing with the slums was that you give them free houses, keep the land, build on it, and make money. For one of my first slum rehabilitation projects in Tardeo, Mumbai in the late ‘90s, we made it possible for those in existing slums to have pucca homes, and also gave the builders sky-piercing towers with sea view for its premium buyers. At the ribbon-cutting ceremony of the first slum-rehousing apartments, women from the slums dressed in their finest sarees approached us with lamps. They were taking our aarti! They treated us like Gods. “Why are you doing this?” I asked one of the ladies. She said; “Do you know what you have done to our lives? We, the ladies in the slum, cannot go to a toilet after the sun rises and before the sun sets, but you are giving us tap water, 24/7.” That’s the impact we have on people’s lives. I really believe that architecture can save this world. My vision is simple. I want every individual in our cities to have access to affordable housing; the basic services of water, electricity, sewerage, as well as health and education. I can’t accept large segments of our population living an insecure life thanks to our restrictive policies that make affordable housing impossible. I want our cities to grow in an orderly and environment-friendly way. We cannot keep increasing the boundaries of our cities, into the farmlands and in turn the forest lands. We need compact, dense cities with vertical zoning. Think about food…water!

AB: We have to address the mathematics of development for habitat versus the mathematics of economics. You’ve been a strong advocate of increasing FSIs. Do you think that will solve the problem?

HC: I reiterate more than 50% of Mumbai’s population live in slums. Most of the land accessible from the city centre in less than one hour is already occupied, leaving us with only two options of increasing housing units- by increasing FSI or forcing large number of households into far away suburbs. The latter is impractical. So instead of debating if FSI should be increased, we should debate how much and where we should increase FSI and what other measures should be taken to support the increase. The real questions are how much additional new floor space should be built, where it should be built and what mechanism should be used to allocate the new floor space between different income groups. More FSI will lower apartment costs. By additional FSI, the common man is also most likely to get the increase in his floor space consumption at a lower cost and have a better standard of living. Above all our housing has to be on par with an average Indian’s earning capacity. We need affordable housing.

AB: Affordable housing is the key. We are also working on a slum redevelopment project through which we intend to provide improved housing for 20,000 to 40,000 families. The priority at the moment are the issues that are raised by our increasing urban population and our patterns of consumption. The need of the hour is to address this issue at scale and address it with a lot of speed. There are a lot of conversations about ‘smart cities’, these are pointless conversations. We have existing cities, we have enough and more land that is within urban precincts. This can be optimised to cater to the needs of our population. We need to contemplate and implement what we can do as a society to optimise space, minimise consumption and conserve resources. Being mindful and treating our own waste, generating our own energy, and reducing consumption is ta pressing need. I feel design should be about reduction and optimisation. The only way for architecture to remain relevant for longer than its period of conception is by creating buildings that are self-reliant – buildings that can function with minimum resource consumption. Don’t you think so?

HC: Land is a precious commodity. And we are already at 10% of our urban coverage which is the highest in the world. We have to increase our forest coverage. How do we do that, is the question! We have to rebuild our cities. It has to be dense, compact, and vertical! We should go for enormous vertical developments. i.e one massive tall building, providing space for offices, retail shops, residential flats, entertainment areas and so on! Since all these would be within a building, we can reduce the distances, thus can avoid roads and vehicular transportation. We should be thinking about vertical transportation with elevators. Thus, we become less dependent on fossil fuel and should look for other means to produce electricity, probably relying more on solar power. This would be, in my opinion, the path to achieve a higher level of ecological development. I would say that it all depends on how we preserve land since land is a very precious commodity which nobody can manufacture. Another important aspect is the cultivation of food. With the increase in population, the demand for food will increase. Hence, the preservation of land and creation of green spaces is very important. We should think of vertical farming. I would say that vertical zoning is the only solution or option for making developments denser that can lead to sustainable cities. Don’t keep on increasing new cities. Restrict to your old coverage. Reduce your old coverage. The cities have grown into the farmlands, while the farmers have moved into the forest land. Now let the forest come into your cities where water is abundant. Instead of creating 100 more smart cities, we must opt for three or four mega cities. I reiterate, we need to plan for denser cities, which could accommodate the majority of people in locations closer to the existing cities, where there is ample water, power and food. Non-agricultural land could be used for intense, dense developments, so that there is less dependency on any kind of transportation. The answer to India’s urban development may not be low rise; high density but high rise; high density! But we must do it economically, ensure it lasts and create a sense of well-being while still reducing consumption.

AB: Architecture must create this sense of well-being for the population at large, and that discourse is absent in the mainstream practice of architecture. Unfortunately, most conversations that we have in architecture are centred around fancy residences, or a commercial space or institutional projects. And that’s where the difference strikes us. You have done the most for, or rather pioneered the concept of real housing. You’ve created habitats at a large scale. And that’s what makes your practice a force to reckon with. No matter what one says, every other conversation in architecture falls flat, because no one has been able to demonstrate it in a way that you have executed it.

ZERO WASTE ARCHITECTURE: THE RELEVANCE AND PRACTICALITY

AB: There’s a lot of conversation around zero waste architecture. But in my opinion, zero-waste architecture in high-rises may not be entirely practical. What are your thoughts on zero waste architecture?

HC: We have championed the art of residential architecture, be it affordable or luxury. For us the most important is design efficiency, and we have reinvented ourselves with time. Today 80% to 90% of construction is in the residential sector. What we try to do in each of our projects is reduce the consumption of materials or rather save 10% of the materials used. Which means that you are going to build 10% more housing with 10% less material and economically by about 10%. Every material is getting scarce, and one has to use these materials judiciously. I think that green or sustainable construction means not just using energy efficient building materials and products in your projects but also emphasizing judicious use of land as much as possible. That for us is Zero-Waste Architecture.

AB: That’s one way of looking at it. The other way would be to use local resources. By local resources I don’t mean mud. You can’t build airports with mud! I mean, locally sourced materials which reduces our carbon footprint. You mentioned that every material is getting scarce. That’s true. Hence the idea would be to use long lifespan materials so that our buildings last longer. If we work with modular, standardised materials like steel and mass timber, we create an opportunity for component recyclability in the coming decades. That’s one of the reasons we use modularity & prefabrication in our projects, it reduces wastage on site, reduces construction time, and offers flexibility. It’s more about changing our patterns of consumption than anything else.

FOR THE COMING GENERATION OF ARCHITECTS

HC: In the last one year, I’ve seen an entirely new breed of architects, and they are good. At any given point of time, there are at least 70-80 interns in my office. But everyone wants a miracle overnight. They are constantly comparing themselves with other sectors. Architecture is a creative field and I feel that architects should be working for pleasure, at least, that’s what I do! I will work till 95, and I still won’t be bored because I like what I’m doing. Don’t run after money. Do good work, and money will follow! Work, be consistent, build your work balance. Bank balance will follow!

AB: Grow your skills. Test your theories by actually working on them. You have to groom yourself till it’s essential to start a practice. That takes time. In India we’re allowed to practice the moment we graduate from architecture school. That is because our denominator for professional practice is low. I would say, spend a few long years working in an established architectural firm, find your voice, find a unique way to say it. That would be the path to follow.

HC: One word of advice for all architects – The future of India lies in how we build, how we build our cities, preserve land, forests, and house all our people. One should be mindful of that. While buildings may have used energy in construction, having enough land and forest and enough trees in the forest, would balance its carbon footprint.