The brief for the project involved an adaptive reuse angle: that of making the existing dilapidated structure usable again, using a limited budget and minimal intervention. The design then places a great emphasis on reclaiming usable spaces within a relatively fluid layout on an open floor plate. This was partially achieved by undoing ad-hoc alterations in the building’s spatial layout, according to its previous life and occupants. Apart from the interior and spatiality of the building, the stern looking exterior of the building is a measured response to several external stimuli. The inward looking nature of the building almost fortified by a hard shell, akin to molluscs, develops in response to acrid air quality, monkeys being active inhabitants of its surroundings, eliminating the scope of expansive fenestrations, and the lack of any significant visual avenues to harvest.

Since the pods are made from steel shipping containers with R-19 insulation and temperature control devices, they can withstand extreme weather conditions, earthquakes, harsh terrain, and security threats. The use of containers allows the CMFs to be easily deployed anywhere. With the clinic already assembled within the container, these can be used as emergency care facilities for Covid-19 patients and primary healthcare centres.

How much time does it take to install LifeCMF in an emergency situation? And does it require high-expertise?

Modules are prefabricated with all necessary furniture and equipment. They can be deployed rapidly, only requiring minimal on-site construction for foundations and joinery between modules. The Mohalla Clinics took 3-15 days to complete, including the time taken for prefabrication and container procurement. The deployment time, however, varies according to scale. The prefabrication takes place in controlled factory environments to ensure an optimum level of construction quality and hygiene. Then they can be installed and assembled with limited labour and machinery.

When was it selected for the London Biennale? Was it showcased online?

LifeCMF was part of the India Pavilion at the London Design Biennale 2021, a selection of solutions against climate change put forth by leading Indian architects and designers. Titled ‘Small is Beautiful: A Billion Stories’, the India Pavilion displayed 150 seminal ideas that were selected through a rigorous judging process spread over three weeks. LifeCMF was also a part of ‘Design in an Age of Crisis’, a gallery of 500 submissions from 50 countries presenting radical ideas that respond to the world’s most pressing issues.

Contrary to a lot of modern buildings that harness the outdoors to create their own microcosms within, the headquarters of Rug Republic, a retail hub for artisanal rugs and soft furnishings, seems to display a staunch confidence in its exclusivity with respect to its outdoors. Through wide and narrow apertures crafted in its corten steel skin, lined with a series of dangling, rust-stained link chains, the building aims at re-interpreting the ‘warehouse typology’ in a post-industrial aesthetic. Minimal daylight is admitted into the rug haven inside, and shipping containers find their place on the site grounds as ancillary spaces. One could go out on a limb and associate the aesthetic with a staged, theatrical sense of a warehouse, as mentioned. When viewed in isolation, it may even underline a dystopian outlook, but the virtue of the design hand dictates anything but, switching the narrative on the monotone buildings around it, and on the architecture of the city.Contrary to a lot of modern buildings that harness the outdoors to create their own microcosms within, the headquarters of Rug Republic, a retail hub for artisanal rugs and soft furnishings, seems to display a staunch confidence in its exclusivity with respect to its outdoors. Through wide and narrow apertures crafted in its corten steel skin, lined with a series of dangling, rust-stained link chains, the building aims at re-interpreting the ‘warehouse typology’ in a post-industrial aesthetic. Minimal daylight is admitted into the rug haven inside, and shipping containers find their place on the site grounds as ancillary spaces. One could go out on a limb and associate the aesthetic with a staged, theatrical sense of a warehouse, as mentioned. When viewed in isolation, it may even underline a dystopian outlook, but the virtue of the design hand dictates anything but, switching the narrative on the monotone buildings around it, and on the architecture of the city.

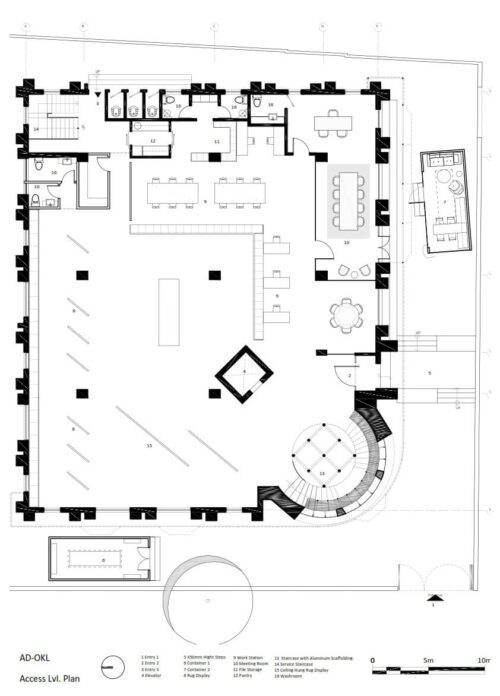

Being located on a corner plot proves another great impetus to the building to put up a distinguished frontage, and a distinct identity in the elevation itself. Near the corner, the entrance to the building is earmarked by a helical staircase that defines a curved aperture at the corner of the building, pronouncing the striations and rows of corten steel that line the façade. The staircase also dictates movement through the building, proving a pleasing contrast from the largely rectilinear layout. A well-defined hierarchy in the spatial organisation places frequently used spaces such as offices and temporary exhibitions on the ground floor, while permanent exhibitions for the company’s diverse products and private office cubicles are accommodated on the upper levels. Two stand-alone shipping containers abutting the building serve as a spillover space for patrons during work breaks or as makeshift meeting rooms. A small terrace on the top provides views of the distant greens.

An overarching philosophy that lends itself tastefully to the building’s design, with a minimalistic approach and a raw material palette, was creating a bare shell to generate a non-intrusive backdrop to celebrate Rug Republic’s exquisite work including rugs and soft furniture, like a concrete canvas displaying art. ‘Skeletons’ for the display and exhibitions comprising temporary interventions including rebar cages and other inexpensive material assemblages against bare black and grey interiors add an additional degree of flexibility to the internal layout. Furthermore, the floors too are lined with fire bricks to allow ease of removal and replacement in the future.

“It’s fascinating to take something forgotten and to give it a new life: This is the century of recuperation. There is no space, no forests, and no water anymore for continuous production of new things. So, (we) take something old and make it special,” states Akshat Bhatt, the founder and principal of New Delhi-based Architecture Discipline on the emergent thought of shaping the new Rug Republic HQ from an ageing, decrepit building. He further muses: “Have we brought ourselves to this? And, even if we have, can we still make it interesting?” Instead of plainly reflecting a grim occurrence of the city’s bustling yet dehumanised industrial belly, it does so impressionably, attempting to create a statement unto itself.